Introduction

Adam: Hello, this is Adam Gordon Bell. Join me as I learn about building software. This is called Corecursive.

Cory: Then we’re like hawks leading ourselves into the full oil well, right? That is the most stupid, awful possible dystopia, right? To make sure people don’t watch TV wrong, we make it illegal to report defects in browsers, are you kidding me? What idiot thought that was a good idea?

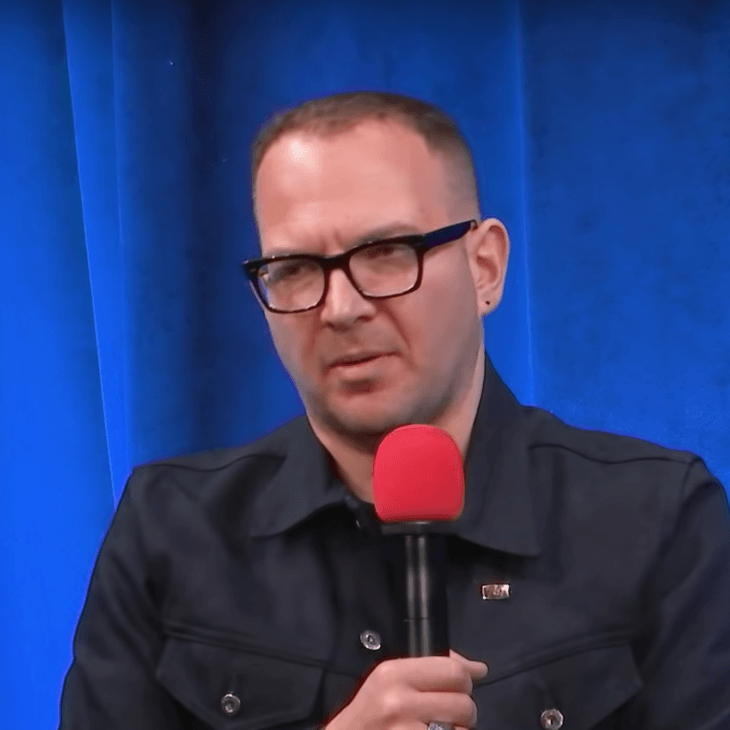

Adam: That is Cory Doctorow. He is the editor of Boing Boing. He’s a science fiction author. I think I’ve read every sci-fi book he has written, I guess even some that aren’t sci-fi. He’s very involved in the Electronic Freedom Foundation, the EFF. And most importantly, for this episode, I would describe him as an advocate for digital civil liberties. I was thinking about how in dystopian visions of the future, the power that governments or corporations have to oppress people are often software and computer networks and cameras, and things that software developers would have a role in building. I think that we software developers, therefore have a big role in kind of shaping the future that we end up in.

This is the topic that I talked to Cory about today. Sometimes I listened to a podcast on 1.5 times or even 2X speed, Cory, I think requires listening at 0.75 speed. He covers a wide breadth of topics, he had some little aside about evidence-based policy that really blew my mind, and a ton of other interesting tidbits. I hope you enjoy the interview. So Cory, thanks for joining me on the podcast, I have a copy of your new book here, which I’m quite enjoying, but I wanted to ask you sort of some high level questions about software and technology and freedom, maybe even. So let’s start with an easy one, so is technology a force for liberation or for oppression?

Technology Good or Bad?

Cory: You know what, I think that the right answer is not about what the technology does, but who it does it for and who does it to. And I think that whenever you see a dark pattern in technology or an abuse of technology, when you pick at it, you find that you’re not looking at a technology’s problem, but a policy problem or a power problem or sometimes you might think of it as like an evidence-based policy problem, which is the kind of policy problem you have when you have power problems. If you can’t examine the evidence when the evidence scores some rich important person’s ox then you can ever ask whether or not the technology is working because if you found out the answer, there’s a pretty good chance that it would undermine the profits of someone who gets a decision and whether or not you get to research whether the technology is working.

You can think about things like predictive policing, right? The idea of predictive policing is that you can use statistical modeling to replace the kind of police intuition which may be laden with either conscious or unconscious bias, and direct policing to places where it’s likely to occur. But the way that these machine learning models are trained is by feeding them data from the very police whom you suspect have either conscious or unconscious bias. And you don’t have to be a machine learning specialist or a mystic to understand, garbage in, garbage out, it’s been an iron law of computing since the first I/O systems. And if you feed bias policing data to an ML system and say, “Where will the crime be?” It will give you a biased answer. And this has been really well demonstrated by a guy named Patrick Ball, who’s a forensic statistician, who runs an NGO called the Human Rights Data Analysis Group.

And mostly what they do are these very big projects like they located a bunch of hidden mass graves in Mexico, they participated in genocide trials in Guatemala, and so on and so on. They use fragmentary statistical evidence to build out larger statistical pictures of the likely unreported human rights atrocities committed during revolutions, wars, oppressive regimes, and so on. But in this case, they decided to investigate predictive policing, and specifically a product called PredPol, which was created by University of California professor, and it’s the most widely sold predictive policing tool in the country. And so what they did was they took policing data from Oakland, California from two years before, and Oakland is notorious for a bias in its policing as well as violence.

And they specifically said, “Given the policing data from two years before, where should we expect to find drug crime next year? Where will the drugs be in Oakland?” And if you look at the map that PredPol spits out for the following year, which given that this was two years old data was the year before and a year ago, it’s just this giant red splotch over the blackest part of the blackest neighborhood in Oakland. And then they took the NIH standard of drug use, which is the gold standard for empirical pictures of where people actually use drugs in America, and they said, “Where is the drug use…” which is to say the drug crime, in Oakland? And it’s this kind of nice Gaussian distribution with a couple little strange attractors, but the data is distributed very evenly across the whole map.

And so you can see how very quickly bias in data can produce bias in conclusions. And so the problem with PredPol is that we asked PredPol where to police without bias, but all PredPol does is make us do more biased policing. But imagine instead that you took this data and you used it as a way to evaluate whether or not there was bias in policing, right? You said, “Okay, well, here’s the empirical data about where crime takes place. Here’s where the machine learning model predicts for crime will take place. Now we know that our police data is producing biased outcomes.” And then you might create an intervention, right? You might try and train the police or you might try and change the racial or other makeup of the police department or some other intervention.

And so now you’re performing an experiment, and you need to evaluate whether it was successful, you can use exactly the same tools to find out whether or not your anti-bias initiatives are working, or failing. And the only difference between PredPol being used to valorize and provide a kind of veneer of empirical face wash to racism and embedded as a permanent feature of policing in Oakland and predictive policing tools being used to root out and eliminate bias in policing in Oakland. It’s who wields the tool, and why they wield it, and not the tool itself. And so, technology is a force for good when we wield it for good. And our ability to wield it for good has been systematically undermined because the people who get to decide how we wield that are increasingly not subject to any kind of democratic controls, they act without any kind of consideration for other important equities in society. And no one gets to investigate whether or not they’re doing a good job or a bad job.

Overcoming Bias and Anti Trust

Adam: And so can this problem be overcome? So I get there’s a perspective you’re saying where you could use the machine learning to look at the bias embedded in the data, so why isn’t that happening?

Cory: Well, I think because Tech has grown up with a radical new form of antitrust enforcement, which has been part of a radical shift of who has how much wealth in our society. So remember that Jobs and Wozniak released the Apple II Plus while Ronald Reagan was on the campaign trail in 1979, right? And the first thing pretty much that Reagan did in office was start to dismantle antitrust protection. As a science fiction writer, I can tell you that he relied on another science fiction writer, specifically an alternate history writer to inform his theories of antitrust, there was a guy named Robert Bork, he’s very famous for not being confirmed for the Supreme Court when Reagan nominated him, who conceived of an entirely fictional account of how antitrust law came to be in this country.

He wrote a fanciful legislative history of it that said that the Sherman Act was written by people who are not concerned with monopolies but were instead concerned only with so called consumer harm, whether or not monopolies were used to raise prices, and everything else was fair game, cornering markets, vertical integration, buying all of your big competitors, buying all of your little competitors, using locking to snuff out anyone who entranced the market, all this stuff that had been illegal under antitrust since day one suddenly became legal again. And so Tech has grown up over 40 years with a steady erosion of antitrust. And now we have things like Facebook, which is the largest tech social media company in the world. It grew primarily by buying its competitors. If you think about what other successes has Facebook had as a homegrown success? There’s pretty much none to speak of.

Same is true of Google, right? Google made search and Gmail, and everything else that they’ve succeeded with is something that they bought, and they would have been absolutely prohibited from buying those other companies, YouTube, and G maps and all of these other companies that they bought, they would have been absolutely prohibited from doing it until Reagan came into being. So we’ve had 40 years, a generation and a half, nearly two generations of antitrust malpractice in America and in the wider world because Reagan wasn’t an isolated phenomenon, Thatcher was elected around the same time and in Canada, where I’m from, we have Brian Mulroney, and they all subscribed to these radical theories that came out of Robert Bork in the University of Chicago, and 40 years later, the internet consists of five giant websites filled with screenshots from the other four.

And it’s not just the internet, right? This week, the screenwriters are firing their agents because there’s only three big talent agencies left, they’re all owned by hedge funds, and they’re screwing their clients. And that’s also true in world wrestling, we’re down to one world wrestling league, and the median wrestler is dying at something like 46 and they’re all treated as independent contractors, and none of them have medical benefits. And so every industry over 40 years has been transformed into this oligarchic structure, and has power is concentrated into fewer and fewer hands, our ability to make policy that reflects pluralistic broad goals, as opposed to the parochial needs of someone who wants legislators to deliver them gifts in the form of laws that enhance their profits instead of enhancing the public good, their power grows and grows and grows.

And so we conduct all of our policy in an evidentiary vacuum. And that means that all of these things that enhance shareholder returns but at public expense sail through with no regulatory scrutiny, that’s true in tech, as it is in every other regime. I mean, the biggest industry in West Virginia, it’s not coal, it’s chemical processing. And the biggest chemical processor in West Virginia is Dow Chemicals and their lobby just filed comments in a docket on whether or not West Virginia should allow increased levels of toxic runoff from chemical processing in the drinking water.

And Dow Chemicals submitted an answer that really tells you that they’re not even trying anymore, that as far as they’re concerned, so long as there’s some reason, it doesn’t have to be a good one, they’ll get what they want because their answer was, “Yes, of course, we can have higher levels of deadly poison in the drinking water because the toxic levels that are approved nationally are based on the average body size of the average American, and people in West Virginia are much fatter than the average American, and so chemicals will be more dilute in their bodies, and besides West Virginians hardly drink water at all.”

Right? That is the answer of someone who’s just stopped caring whether or not their ideas past the giggle test, who knows that so long as they can write down any reason next to the box where they tick, I object, that will carry the force of law. And so that’s the world we’re living in now. Now, does technology have a role to play in fixing it? Absolutely, right? What technology is not going to do is it’s not going to allow us to, as some people thought in the early 90s, we can’t use cryptography to create a separate parallel society in which we can live free from the interference of dum dums who don’t understand technology while tyranny grows up around us, right? The term rubber-hose cryptanalysis, I believe Julian Assange actually coined it, refers to the idea that if you don’t have democratic fundamentals in the society you live in, you may have a key that is so long, that it couldn’t be guessed, not even if all the hydrogen atoms in the universe were converted to computers and all they did between now and the stelliferous era was try to guess keys.

But it doesn’t matter if the person who knows the key can be dragged into a little soundproof room where there’s a guy with a howling void where his conscience should be, and a pair of tin snips, right? Because that person will find out the passphrase anyway. And so what is it that technology allows us to do? It allows us to build a kind of temporary shelter that will hold up the roof after the support pillars have been removed by 40 years of increased oligarchic policy. And we can hold up the roof while we erect new pillars, while we create new democratic fundamentals. Because what the internet gives us is the power to organize like no one has ever organized before. Facebook is a machine for finding people who have hard to find traits in society, whether that’s people who are thinking about buying a refrigerator, which the average person does two or three times in their life, or people who want to carry tiki torches through Charlottesville while dressed up as you know Civil War larpers chanting, “Jews will not replace us.”

Or people who have the same rare disease as you or people who went to the same high school as you or people who care about this stuff. Networks allow us to find people who care about the same stuff as us and coordinate our work with them in ways that exceed the best systems that we’ve had through the whole histories of the world. And cryptography allows us a degree of operational security that while imperfect, and while subject to democratic fundamentals, nevertheless creates a temporary and usable edge that we can exploit to give us the space to operate while we embark on the long and vital project of reforming our society to reflect the needs of the many and not the few.

Elon Musk Punching Things

Adam: So if I understand, what’s a good way to say that? Power has coalesced over time since these antitrust laws are gone and you’re saying it’s not the kind of cyberpunk vision of people should abandon society and build an anarchist commune, but that they should use their power to network, to change things, is that the vision that you’re putting forth?

Cory: Yeah. We have a systemic problem and it will have a systemic answer, right? It will not have an individual answer. We’ve had a 40 year long project to convince us that all of our problems have individual causes and individual solutions. The problem with climate change is whether or not you are good at separating your waste before you recycle it, and that if only you were better, then we wouldn’t be all drinking our urine in 30 years, right? And the reality is that you can recycle everything, you could go down to zero waste, right? And we would still not solve climate change. The chances are that your biggest contribution to climate change is your commute and the only way you are going to solve your commute is with public transit. And you cannot personally create public transit, right? You will never build your own subway system. I mean, this is the fundamental flaw with Elon Musk, right? Is he thinks that he’s Iron Man, right? He thinks you can just punch things until they’re fixed, right?

That you can just build a boring machine and dig a tunnel, and that will solve transit. And the reality is that these are pluralistic problems with pluralistic solutions. They’re problems that emerge out of collective action, and they have collective solutions. But the internet is the greatest collective solution tool we’ve ever had. I mean, think about just source control, right? Version control, version control or Wikis allow people to pool their labor in ways that are infinitely more efficient than anything that existed before them, right? Imagine trying to write Wikipedia without a Wiki, right? Where instead you were using couriers shipping giant filing cabinets with the latest revision around to everyone who wanted to read or edit it several times a day, right?

[inaudible 00:16:27] control used to work before we had source control, where either everything was written by one person, and that put a limit on how complex a system could be, or only one person at a time could work on the system. And you generally had to all be under one roof, or you had to plan it in advance so that you knew that the Austin office was working on one part in the New York offices working on another. We now have through just CTRL+Z and revert and check ins and rollback, all of those things allow us to pool our labor using these informal networks that before would have needed rigid, well defined hierarchical systems that were capital intensive and that put a limit, right? On how much work you could do because there was a certain amount of sitting around with your thumb up your ass waiting for the courier to arrive with the filing cabinets full of Wikipedia revisions or waiting for it to be your turn to work on the code.

And now we can collaborate in ways that put the dreams of theorists of collective action to shame. When you think about Adam Smith writing about the pin factory, where you have an assembly line where people are making pins and one person stretches the wire and one person slips in and so on. And he’s rhapsodizing about this incredible efficiency relative to the individual artists and working in their workshop all on their own, how we’ve managed to decompose a complex process into a bunch of individual steps. And now you think about how we no longer even need to perform those steps in order, the people who perform them don’t need to know each other, they don’t even to know that each other exists, they don’t have to exist in the same place or in the same time, right? How many times has some hacker been like, “I need to solve a problem.”

And they Google it and they find some old abandoned code sitting on a GitHub project somewhere that solves half their problem, and they sync it with their computer and they are now collaborating with someone who might even be dead, right? Who’s long gone. And that is an amazing thing, right? That is what technology buys us. And so as we sit here confronting this world, that is in the grips of an uncaring, depraved in their indifference oligarchy who make policy to benefit themselves without regard to everyone else, to the point where we now risk literally the only habitable planet in the known universe. So one thing we have going for us that no one has ever had in a struggle like this before, is the ability to coalesce groups and mobilize them in ways never seen before.

Hyperbolic Discounting

Adam: That’s a powerful vision. So there’s this joke, I don’t know the root of it, but it’s software engineering joke, right? So it’s, an ethical developer would never write a method called Bomb Baghdad, they would write it called bomb city and it would take the city as a parameter. So the joke is about the idea that-

Cory: Yeah, I get that joke. Yeah, I understand the joke.

Adam: [inaudible 00:19:23] condescend to you.

Cory: Yeah, no, no, no. No, I think that what you’re describing is not just maybe an unforeseen consequence, but rather the way that we seduce ourselves into doing things that we know are wrong because we overweight the immediate instrumental benefits of getting a paycheck and underweight the long-term consequences of lying on your deathbed realizing that you participated in genocide, that’s a common problem, I mean, that’s why people smoke, right? They overweight, the pleasure of having a cigarette now and they underweight the long-term consequences of dying of lung cancer, behavioral economists, they have a name for it, right? A hyperbolic discounting. And it’s when you over discount immediate consequences and undercharged for long-term consequences. And this is an old problem of our species, but it’s a problem that we often rely on democracies to solve, right? One of the things that democracies can do is act as a kind of check against that convenient rationalization by creating policy firewalls that sit between you and the rest of the world, right?

Either some of those might be minortory, like, “Oh, well, their short-term benefits are very high and the long-term costs are a long way away so I don’t need to worry about it.” But when society adds a criminal penalties with jail sentences for people who knowingly participate in this kind of thing, well, then maybe it changes your calculus about whether or not you should be doing it, right? There’s other ways of doing it that don’t involve coercive state power, there’s a thing called the Ulysses pact, right? So if you’ve read your Homer, you know that Ulysses was a hacker who went sailing around the sea, and who didn’t want to do things the way that that normies did, and wanted to do things the hacker way. And so when you sail through the sea where the sirens are, you know that the sirens, their song will make you jump off the deck and drown yourself.

And so the standard OSHA protocol for navigating those seas is to fill your ears with wax so that you never hear the sirens. But being a hacker, Ulysses is like, “I want to hear the sirens and I want to not drown.” And so he comes up with an alternate protocol, which is that he has his men tie him to the mast so that when the sirens start singing, although he’ll want to drown, he can’t, he can’t throw himself in the sea, and this is the Ulysses pact, it’s when you take some action in advance of the moment in which you know that you are going to be tempted to block yourself from temptation, right? It’s why you throw away all the Oreos the day you go on a diet, you can still go get Oreos, but you’re raising the transaction costs.

But it’s also things like why when you start a company, you irrevocably license your code under something like the GPL, because someday, your VCs are going to show up at your door and they’re going to say, “Well, those 20 people that you convinced to quit their jobs and trust their mortgage and their kids college funds to you, if you want to make payroll for them next week, you’re going to have to close the source that you promised the world would be open.” And you can say, “You could threaten me all day long, I’ll tell you what, I can’t close the source. It’s an irrevocable license.” Right? And so these Ulysses packs are one of the ways that we guard our strong self against our weak self, right? It’s a way that we can reach into the future and change the calculus that we make about immediate benefits and long-term costs.

Wyoming’s Authorized Bread

Adam: That’s a great idea. You had this character in your book, she’s not a main character, but this [inaudible 00:22:51] who was working on the software, right? For a bread machine. I’m wondering, what would you tell her to do if you were speaking to her? She’s a software developer who’s building something that I believe you think is bad, right? But she’s not a bad person, how would she even know what she’s doing is bad?

Cory: Well, I mean, part of the story is her discovery that she’s bad, and we should mention that it’s not just a bread machine, it’s a toaster that is sold at a subsidy, but it’s locked to a certain kind of consumable that uses a vision system, so only heat authorized meals and toast authorized breads, little toaster oven. And it’s being used as an extractive mechanism to take poor people who are in subsidized housing and these appliances are being non-consensually installed in their subsidized housing as a condition of their residency, and thereafter dooming them into a spiral of debt. And as she comes to realize this stuff, as she comes to realize more viscerally what’s going on, she meets people who are involved in it, she has to come to grips with their conscience.

So the first thing that she does is she tries to help them subvert it. And then the second thing that she does is she tries to co-opt the individuals who she has come to like and make them part of the system. She basically gets them a job offer from her big terrible company, thinking that so long as she can bring along the people who matter to her, all of the people that she hasn’t met who also suffer under this system won’t matter. And when the person whose story it is, the refugee woman is Selena, who she tries to get a job offer for, as they reject this job offer and say, “No, it’s all of us or none of us.” She then helps them more permanently subvert the whole system. She helps them work out how to make a VM that can respond to challenges that nonces from the server that make it look like they’re running unmodified firmware, and meanwhile, she helps them come up with firmware modifications that let them reconfigure the toaster ovens so that they can toast any damn bread they want.

Adam: So I really enjoyed the story and I found that you had this thing called the bad technology adoption curve.

Cory: Yeah.

Adam: What is that?

Cory: Okay, so when you’ve got a terrible idea about technology, you know that it’s going to generate a lot of complaints. And so you need to try it out on people who nobody is going to listen to when they gripe. And so you have to find people with no social agency as your beta testers. And these non-consensual beta testers, we draw them from the ranks of children, mental patients, prisoners, people receiving welfare benefits then we move up to blue collar workers, and eventually white collar workers once we’ve gotten the kinks out, and once we’ve normalized whatever terrible idea we have about technology, and that means that we can actually care a little into the future.

It’s a bit weird, because for the most part, we can’t know what the future holds, science fiction writers in particular, have no idea what the future holds, which is good news because if the future were predictable then what we did wouldn’t matter. I believe that what people do matters, we change the future by our actions. And so we can use these kids though, and other groups of people who are disenfranchised, to get a little bit of insight into what our future holds because, all other things being equal, if we figured out a way to make kids lives miserable with technology, in a few years, we’ll be doing it to adults, too, right? If you think about, say, just surveillance cameras, right? Surveillance cameras were once a thing that we’re literally limited to maximum security prisons and now they’re things that we pay Google to install in our own houses.

And so that’s how these adoption curves work, right? So by making this a story about refugees with the story, Unauthorized Bread, I was able to kind of make more vivid the underlying tale that we are living through when we say, “Well, it’s okay and legitimate for Apple to decide who you can buy your apps from. And it’s okay and legitimate for HP to decide who you buy your ink from. And it’s okay and legitimate for GM to decide which car parts you can install on your engine.” Because now GM is using cryptographic handshaking to validate new parts when they’re installed, and even if the part is fully functional and equivalent replacement for the OEM part, GM engine can still reject, it can still force you to buy the OEM part.

And if the dead hand of the manufacturer rests on a product after you buy it, and can force you to arrange your affairs to benefit the manufacturer shareholders, even at your own expense, then you don’t own property anymore, right? That makes you a tenant who’s subject to a license agreement or a lease, not an owner, owners, they’re Blackstone on property, the classic texts that you read when you do a first year of property law course. Blackstone describes property as that which man enjoys sole and despotic dominion over to the exclusion of every other man in the universe, right? That’s not like the EULA, a EULA runs counter to that, a EULA that says, “By being dumb enough to use this product, you agree that I’m allowed to come over to your house and punch your grandmother and wear your underwear and make long distance calls and eat all the food in your fridge,” is not what Blackstone had in mind when he talked about property.

Adam: So what about services, right? Like Netflix versus owning a DVD? Do you see that as like a decrease in our rights?

Cory: Well, it depends, right? It’s not Netflix in a vacuum, but Netflix plus DRM, for sure. So historically, copyright has been what they call a bundle of rights. So there’s a bunch of things that you get as a copyright holder and there’s a bunch of things you don’t get as a copyright holder. I mean, obviously, being a broadcaster or someone who licenses work for broadcast means that someone can’t record the broadcast with their VCR, and then sell the VHS cassettes, but they sure as heck can record it with their VCR, lend the tapes to their friends, store them forever and never have to go to the video store to buy your VHS. This was actually decided on by the Supreme Court in 1984 in a case called Sony versus Universal, the Betamax case.

And what happened after the Betamax case, after we had this era in which technology that might be used to infringe copyright, but it was also widely used to do things like copyright permits that were accepted by copyright is that we passed this law called the Digital Millennium Copyright Act or DMCA, and it’s a big gnarly hairball of copyright, but the relevant clause here is section 1201, and that’s the one that makes it illegal to tamper with DRM even if you are doing something lawful. Recording Netflix totally lawful, right? But breaking [inaudible 00:29:41] radioactively illegal, trafficking a tool that lets you record Netflix without Netflix’s permission, if that tool bypasses the DRM, that’s punishable by a five year prison sentence and a $500,000 fine.

So normally what you expect is if a company like Netflix comes into the market with a bunch of offers, some of which are fair, and some of which are unfair, and the unfair ones are things like, “Well, you can’t record it and watch it later and you can’t decide what device you watch it on, you can only use devices that Netflix has blessed,” and so on and so on that you would expect that other manufacturers would enter the market to correct that, in the same way that if your car came with the cigarette lighter fitted with a special bolt that needed a special screwdriver to remove it, and that bolt was there to stop you from using a third party phone charger, and you had to buy their phone charger which cost like $200 or would only charge certain brands of phone, you would expect that the next time you went to the gas station, next to the giant fishbowl of $1 phone chargers would be another giant fishbowl full of 50 cent screwdrivers to remove that bolt, right? That’s how markets usually function.

But because of the DMCA, companies have figured out how to bootstrap themselves into something that you might call felony contempt of business model, right? Where once you add a one molecule thick layer of DRM to a product, then using that product in a way that advantages you instead of the manufacturer becomes a literal felony. And so Netflix is fine as far as it goes, but Netflix plus DRM means that a bunch of features that would otherwise be legitimate are off limits. Now, that’s like the opening act, that’s just the warmup because the real problem is that the DMCA is so broadly worded, and has been so widely abused to produce bad jurisprudence, that the DMCA now stretches to prohibiting independent security auditing, because when you reveal defects in a product that has DRM in it, you make it easier for people to circumvent the DRM.

And so the upshot of that is that we have this growing constellation of devices that represent an auditable attack surfaces that will contain defects because things contain defects, the halting state problem is real. And those defects can be researched, discovered and weaponized only by criminals. And good guys who in good faith discovered those defects can only report those defects to the extent that they do so with permission and under term set by manufacturers [inaudible 00:32:17] when those defects are revealed. So we have made companies that [inaudible 00:32:21] own products. And this goes way beyond whether or not you can record Netflix, or whether there’s a competitive market, this goes to now that we have DRM in browsers, which is standardized by the W3C, a couple of years ago, we now have two billion browsers in the field that have unauditable attack surfaces that can be used to control everything you do with a browser.

So some of these are control surfaces for actuating, sensing IoT devices, so they may be a vector or a gateway for inserting malware into industrial control systems, or into car engines or into pacemakers, all of which have browser-based control systems, or it may be used to compromise everything you do with your browser, your banking, your love life, your family life and so on, and so on. And so that’s the real hazard here, right? The entertainment industry side of things, “Whatever, I make my living from it, that’s fine.”

I’m a science fiction writer, I hope that we will have good rules for my industry, but honestly, if we decide to allow policy designed to protect entertainment that helps you survive the long slog from the cradle to the grave without getting too bored, and if we take that and turn it into the basis for instituting a kind of totalitarian control in our networks, then we’re like hawks leading ourselves into the full oil well, right? That is the most stupid, awful possible dystopia, right? To make sure people don’t watch TV wrong, we make it illegal to report defects in browsers? Are you kidding me? What idiot thought that was a good idea?

Why Software Has Power

Adam: There’s something I’m not clear on, right? So these are a lot of problems to do with legislation around technology, but they’re all focused on technology and I’m wondering why is software so important? Nobody envisions a dystopia where regulations around E-cigarettes or something lead to a horrible end result? Why is software something that has that much power?

Cory: Well, I think that there’s two things going on, right? One is that the tech industry is co-terminal with the dismantling of antitrust. So we’re just the first industry that has had this terrible policy. And if you want to see how things can go horribly wrong in domains that have nothing to do with software if they’re not regulated right, just think of food safety, right? Cholera will kill you dead as will listeria, right? And in ways that are much more immediate and literally visceral than any software bug, right? My grandmother was a war refugee, she was a child soldier in the siege of Leningrad and she married my grandfather who she met in Siberia, he was a Pole and my dad was born while they were living as displace people in Azerbaijan, and then she lost track of my grandfather, and ended up in Poland for a while with his brother.

And the only Polish she really ever learned was how to curse in Polish, so it’s the only Polish I know. And the only Polish curse word I know is [foreign languange 00:35:14], which just means cholera. That’s how terrible cholera is, it’s the all purpose thing that you say when you’re angry, right? Cholera is really bad news. And so evidence-based policy is only possible to the extent that we have pluralistic governance and not oligarchic governance. And we haven’t had that, we’ve been losing that one drib and drab at a time for 40 years, and we’re at a pretty low point right now. But then the other thing, of course, is that software does have a special nature, right? I’m not a tech exceptionalist but I do think that both software and networks, as they’re currently construed, have a special nature that regulators struggle with.

And I think that that nature is in its universality, right? Prior to the Turing completeness, prior to a Von Neumann machine, you had these specialized mechanical or electronic calculators. If you wanted to tabulate a census, you built one machine, and if you wanted to make an actuarial table, you made a different machine and your ballistics table would be on a third machine, and short of dismantling the machine down to the component level, there was no way to repurpose one machine to do the other kind of computation. And what Turing gives us is this idea of completeness, of being able to build a single universal machine that can compute any instruction that we can express in symbolic language. And we go from, if you can imagine our paleo computing forefathers and foremothers struggling to wire together a different machine for every purpose, and then going, “Oh, my goodness, we figured out how to make one machine that does it all. This is incredible, It’s like who knew that this was possible?”

Now, we actually struggled to get rid of Turing completeness, right? There are so many people who would love to build Turing complete minus one, right? Or some limited Turing completeness set, right? Like, “Make me a laser printer that also won’t run malware.” Right? We don’t know how to do that. And periodically, people show that you can [inaudible 00:37:16] of this research on HP ink jets, where the way that you update an HP inkjet’s firmware at least five years ago, was that in the PostScript file that you sent to the printer, you had a comment line that said new firmware blob begins here, and it [inaudible 00:37:34] just everything between that and the end firmware blob and flashes ROMs with it, no checks.

And so literally, I could send you a file called resume.doc, hidden in 100 lines of code, hidden, not visible, and when you sent it to the printer to print out my resume, your printer would be flashed with my new firmware, which would then do things like open a reverse shell to my laptop out of your corporate firewall, crawl your network looking for zero days, compromise every computer it could find, scan every document that was printed for credit card numbers, and make sure to flag those and send them to me. I mean, just awful things. And so people would love it if you could make a computer that was almost Turing complete or even just a programming environment that was almost Turing complete. I remember when it was kind of big news that someone figured out how to make PostScript Turing complete, but then a couple of years later, someone presented research showing that Magic the Gathering was Turing complete, [inaudible 00:38:34] a big deck of cards.

So Turing completeness goes from this thing that was a miraculous discovery and rare and precious to something that’s almost like a, it’s like a nuisance, an unavoidable nuisance. It’s like pubic lice or something, right? We just can’t get rid of it, it’s in all of our systems. I go to Burning Man and they say that glitter is the pubic lice of the playa, because some people insist on putting glitters on their body, and once someone is wearing glitter, everybody ends up wearing glitter. The Turing completeness just keeps creeping in. I remember seeing a presentation, I think, at a CCC where someone stood up and they said, “I was investigating this toy programming language that came with a new social network.” This is long enough ago that we still had new social networks, back before people were like, “No, no, no Facebook will just kill you, don’t make a social network.”

And there was a little toy programming language to animate sprites on your page, on your homepage on this social network, and it had an X and a Y, and a speed and just a couple other commands, looping, really primitive structures. And then like, “I figured out how to combine all of those commands to create Turing completeness. And I wrote a virus and I now control all the pages on the entire social network.” Right?

Adam: That’s awesome.

Cory: So it would be so great if we could figure out how to not always be Turing complete, but we can’t. We also can’t figure out how to make an internet that routes all the messages except for the ones that we don’t like, or all the protocols except for the ones that we don’t like, or connects all the endpoints except for the ones that we don’t like, not because this wouldn’t be totally amazeballs, but because that is not how the internet works. The reason the internet is so powerful and flexible is because you can hide protocols inside of other protocols, you can proxy and route around blocks, we can do a bunch of things that irretrievably run counter to this. And my friend Catherine Moroney, she says every complex ecosystem has parasites. The only systems that we’ve ever had that didn’t have these universal properties were systems that were monocultures like CompuServe, right? Where CompuServe by dint of being disconnected from everything else, by not having to federate, by being able to control all the services that it rolled out, CompuServe was able to attain a high degree of control over what its users did.

But that happened at the expense of being able to be useful to more users than it was ever able to command. The reason that the web grew is not because everybody bought computers, everybody bought computers because the web grew, and the reason the web grew is that we let anyone connect anything to the web and all of a sudden, there was a reason for everyone to get online. And so this is the underlying problem for regulators because regulators are accustomed to thinking of complicated things as being special purpose, and of special purpose things as being regulatable, right? If I say to you, “Distracted driving is a problem, we have to ban car stereos that can interface with telephones.” You might say, “That’s a terrible idea.” You might say, “It’s not supported by the evidence.” But you wouldn’t say, “Then it won’t be a car anymore.” Right? But if I say to you, “You need to make a computer that can run all the programs except for this one that really irritates me.” It doesn’t matter how sincere my irritation is, you can’t make that computer, right? It won’t be a computer anymore.

Sorry Turing

Adam: Now that’s interesting. In fact, that’s the problem, I guess, from the regulatory perspective, but it seems like that’s also the solution to the oppressor elements, right? And I think it comes up in this toaster story as well, right? If you can’t restrict what these computers can do, because they’re Turing complete, it’s like, “Hey, thanks, Turing, sorry we were addicted to you, but now I can unlock whatever we got.”

Cory: Yeah, I mean, that is the amazing thing that we get from technology, technology giveth and technology taketh away. I think that it’s important to note when we talk about regulators that there’s one other dimension here, which is that regulators are perfectly capable of making good policy about complex technical realms that they don’t personally understand, right? The fact that you are not dead of a foodborne illness and that yet there are no foodborne illness specialists in Congress tells you that we can make rules, even though we don’t have the individual expertise embodied in the lawmakers. That’s why we have things like expert agencies, and those expert agencies in theory, their oversight is by people who are not partisans for the industry that they’re supposed to be regulating, and instead are watchdogs.

And so when you have that working well, it works really well. And oftentimes, even very thorny questions can have both empirical and political answers, and even the political answers can be informed by empiricism. So my favorite example of this is the guy who used to be the drug Tsar of the UK was a guy named David Nutt, he’s a psychopharmacologist. He was fired by Theresa May, now the Prime Minister, back when she was Home Secretary, and not undertook a redrafting of the way that the drug authority scheduled potentially harmful recreational drugs, the Schedule A, Schedule B, Schedule C. And what he did was he convened an expert panel of people who had diverse expert experience in this, and he asked them to rate all of the drugs that were in the pool, in the mix, using their best evidence, using the studies that they’ve done themselves or the literature.

He asked them to rate how harmful each drug was to the user of the drug, the users family, and the wider society. And then they did statistical modeling to see which ratings were stable overall regardless of how you weighted those three criteria, because some drugs just stayed in the same band no matter how you prioritized harm to self, harm to family, harm to a wider society. But some of them moved around a lot, depending on how you rated those different priorities.

And so Nutt then went to the parliament and he said, “All right, some of these drugs, you don’t get to make a choice about, right? We know where they go because there’s an empirical answer to how harmful they are in this schedule. But then there’s some drugs where your priorities will inform where we put them, we’re not going to let you tell us where they go, but we’re going to let you tell us what your priorities are. And once you tell us what your priorities are, which is a political question that has no empirical answer, we can tell you empirically where these drugs should be scheduled based on your political preferences.”

So lawmakers are perfectly capable of being informed by experts and still making political decisions that reflect domains or elements of regulation that have no one empirical answer. And the reason we don’t have that today with our technology is not because lawmakers are ignorant, and not because we’ve fallen from grace, right? Not because we’ve lost our ability to reason, but because as Upton Sinclair said, it’s impossible to get a man to understand something when his paycheck depends on him not understanding it. Lawmakers rely on a money machine from industry to get and keep their seats, and then they rotate in and out of industry when they finish their stint in Congress, and that’s also true of regulators.

And it’s true in part because of concentration, when you only have four big companies left in a sector, obviously the only people who are qualified to regulate them, to even understand how they work, is going to be someone who’s an executive with one of them, and probably an executive with lots of them, right? It’s not just that like Tom Wheeler, who was Obama’s FCC Chairman was a former Comcast executive, we know that Ajit Pai, who’s Trump’s FCC Chairman, is a former Verizon executive. But if you look at their CVs, you see that they worked for several of the four remaining giant telcos or five remaining giant telcos. And moreover, they’re like godparents to executives at the other telcos because everyone else is an alumnus of one of those companies, they are married into them, they are intertwined with every single company left in their industry.

And so those people they may have the technical expertise to be regulators and answer empirical questions but they have so many conflicts of interest that their answers must always be suspect. And so this is not just about this character of software and its plural potence, it’s also about the character of the moment we live in, the moment in which software has become important, and it’s this moment in which we have lost the ability to reason together and come to empirical answers because we’ve chosen to turn our back on that part of our regulatory process.

Adam: Wow. So one question I have just to wrap things up is sort of, what do I do? Me, myself? you’re saying there’s a pluralistic solution of us all coming together, but what steps do I take to bring in this internet culture, to make sure it stays around and it doesn’t become this oppressive? What can a person do? What can somebody who is a software developer or somebody… Can we help put the future in the direction of open internet, of a non-oppressive regime, et cetera?

What To Do?

Cory: Yeah, so I’m a great fan of a framework developed by a guy named Lawrence Lessig. He’s one of the founders of Creative Commons, cyber lawyer, really, really smart and wonderful guy. And he talks about how the world is regulated by four forces, there’s code, what’s technologically possible, there’s law, what’s legally permissible, there’s norms, what’s socially acceptable, and markets, what’s profitable, and that all four of these forces interact with one another to determine what actually happens. Things that are technologically impossible don’t happen, right? You could have a terrible law that says everyone is allowed to carve their name on the surface of the moon with a green laser, but until we have green lasers that can carve your name on the surface of the moon, the law can say whatever it wants, and nothing is going to happen as a result.

So what’s technologically possible, obviously has a huge shift. What’s legally permissible changes what’s profitable, right? It’s not that things that are illegal can’t be profitable, but the transaction costs of being a drug dealer, for example, include a whole bunch of operational security measures that take a big chunk out of every dollar that you earn, because you can’t just go on Craigslist and say, “I have heroin for sale and here’s my house and come on buy and get as much as you’d like.” And so that makes the whole process a lot more complicated and harder to manage, and much more expensive and less profitable. Things that are profitable, those things are easier to make legal, right? If you are making so much money from what you do, that you can spare a few dollars to send lobbyists to Congress, or to get your customers to agitate on your behalf or both, then it’s easier for you to make what you do legal and to expand the legality of what you’re doing.

And norms change what’s profitable as well as what’s legal, right? It’s very hard to pass a law that flies in the face of norms. One of the reasons that we’re seeing marijuana legalization all over the place is that normatively smoking marijuana has become pretty acceptable. Same thing with gay marriage, right? Banning gay marriage changed, in part, because normatively being gay changed, right? The social acceptability of being gay changed, and so the law followed from that.

And so all of these things swirl around and one of the implications of this is that when you find yourself hitting a wall with trying to affect change in the world, you can ask yourself, “Which of these axes was I pushing on?” Because you may have run out of headroom or freedom of motion in one axis, right? You may have hit the boundaries of what the law can do, but maybe you can make a technology, right? Not a technology that allows you to exist indefinitely outside of the law, but a technology that allows you to agitate for a change in the law, right? Or a technology that allows you to change normatively how we think about the law.

Say, an ad blocking tool, right? So one of the things that I think is going to be hugely effective at pushing back on the expansion of control over browsers is that ad blocking is the most widely adopted technology in the history of the world in terms of time from launch to now, and it’s the largest consumer revolt in history. And it’s such that the enforceable EULAs on browsers plus DRM make it harder to block ads, then you will see more scope for a legal change to legalize ad blockers that have to go beyond what they do now, that have to be able to violate EULAs, even though that puts them in conflict with the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, that have to be able to circumvent DRM, even though that puts them in conflict with the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, and so on. Because normatively, people want to keep their ad blockers, and so legally, we will open up the space for legal reform.

And technologically, we got there because someone made an ad blocker and put it in the world, right? So all of these things swirl around and around. And so when you’ve run out of headroom in one domain, try seeing if you’ve got a little freedom of emotion in the other. I live in Los Angeles now and I’m one of nature’s terrible parkers, and every now and again, I have to parallel park my car, I never really owned a car before now. So every now and again, I have to parallel park my car, and when I do, I’m one of those guys who has to twist the wheel all the way over to the right, and then tap the gas pedal and get one half inch of space from doing that, and then I turn my wheel all the way to the left and I tap the gas pedal and I put it in Drive and I get another quarter inch, and inch by inch, I am able to work my way into parking spots that people with better geometric sense than me can get into in a few seconds.

But [inaudible 00:52:22] in the stepwise way, I’m able to finally get my car up to the curb. You can think of it as being a kind of hill climbing exercise, when we’re writing software and we have to traverse a computational terrain that is so complex that enumerating it would take so long that by the time we were done, it would have changed so much that we would have to start a numerating it all over again, we have another way of solving a problem, right? We do it through hill climbing, we analogize a software agent to something like an ant, an insect with only forward facing eyes, and so it can’t sense the gradients that it wants to ascend by looking at them. But it can pull its legs, and it can ask which direction that it knows about, will take it towards higher ground.

And it can proceed one step in that direction, and then pull its legs again to see which leg is now standing on the higher ground. And as it attains each step, it finds another step that it can take. And when it runs out of steps, it’s reached its local maximum, it may not be the highest point it could have attained if it could see the whole landscape, but it can see how to get to the highest point available to it from where it’s starting right then. And so we can use hill climbing as a way to think about our tactics as we move towards the strategical of a more pluralistic, fairer society where technology is a tool for human thriving instead of human oppression. You can ask yourself at any given moment, which steps are available to you legally, technologically, in a market framework or normatively, is there someone you can have the conversation with? Is there a company you can start or you can support? Is there a bill pending that you can write a letter in support of or campaign on behalf of?

Is there a politician running was good ideas? Each one of these advances the cause, and I think the reason that we’ve been cynical before when we think about this stuff, is we think of each one of these as an end instead of a means, right? “If only we can pass the law, then we will be done.” Well, no, if we can pass the law, then we will have opened up some normative space, and if we open up some normative space, maybe we can open up some market space, and if we open up some market space, maybe we’ll be able to invest in some new technology and open up some new code space. And so this is my framework for action, and there are a bunch of groups that operate on these principles and try to bind together the labor of lots of people to make a difference in the world. So obviously, Electronic Frontier Foundation is one that I work with, they don’t pay me, I get paid as a research affiliate of MIT Media Lab, and they pay for the work I do at EFF.

There’s also the Free Software Foundation, there’s also Creative Commons, there’s also the Software Freedom Law Center, there’s also the Software Conservancy. I mean, there’s so many organizations, the Internet Archive, and so on and so on that are doing excellent work, and depending on where your proclivities lie, they either need your code or your money or your name, or for you to show up at a rally or to talk to your lawmaker, or to vote and put your support behind a bill, right? And all of these axes, code, law and norms and markets are being deployed by these organizations all the time. And it’s a matter of working with them to help them on the actions that they’re doing, and then working in your own life to advance the cause where you are now.

Adam: that is a great call to action. I really like that. I personally, am a member of the CCLA, the Canadian Civil Liberties Association.

Cory: Yep, just sued the Government of Canada, the province of Ontario and the City of Toronto over Google’s so called Smart City project with Sidewalk Labs.

Adam: Yeah, yeah. It’s important to have these organizations that can take on corporate interests, I feel like.

Cory: Yeah, yeah. I mean, we broke a story on Boing Boing that the Sidewalk Labs had secretly attained approval to build their so called prototype city on a plot of land that basically covered the entire lakefront of Toronto, was supposed to be one little corner of the city, and in secret, they’ve gotten the whole city, and then when we broke the story, their PR person wrote us a bunch of emails where they basically lied about it, and they said, “Oh, no, no, you’re misreading the relevant documents.” Finally, they admitted it. And that’s part of what spurred this lawsuit because once you’ve got really the whole lakefront covered by Google’s actuators and sensors, under continuous surveillance, the CCLA, the Canadian Civil Liberties Association was able to argue that this violated Canadians rights under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Cory’s New Book

Adam: Yeah, I didn’t know about your role in this, but that is amazing. So I want to be conscious of your time. So yeah, I think everybody should obviously check out those resources, I’ll put some links and your new book, Radicalized, which is super interesting, kind of it paints a very dystopian picture of some of the concepts we’ve talked about here.

Cory: I like to think of it as a warning rather than a prediction, right? The idea here is, and not all of them are dystopian, I mean, Unauthorized Bread’s got a happy ending, and so does Model Minority, Radicalized has a little more ambiguous ending and depending on who you’re rooting for, and a mask of the red death, you can make the case that at least someone got a happy ending out of that. But I think of them as warnings, right? As ways of kind of having the thought experiment, “What if we don’t do anything about this?” Or, “What if we let things go wrong? What’s at stake here? Is this a fight that we should really join?” Not as predictions, right? These are not inevitable, these are only things that we can choose to allow to come to pass or that we can intervene to prevent.

Adam: Yeah, they’re great. I really liked the Unauthorized Bread, I think that’s my favorite.

Cory: Oh, well, thank you so much. I really appreciate that.

Adam: We’ll take a minute for fandom. I’ve read so many of your books, so it’s quite an honor to talk to you.

Cory: Oh, Thank you.

Adam: One book that stayed with me a long time was this someone comes to town and someone leaves, is that what it’s called? Something like that.

Someone Comes To Town, Someone Leaves Town

Cory: Someone leaves town. That’s from an old saying about screenwriting, that there’s only two stories in the movie, someone comes to town, someone leaves town.

Adam: Oh, I didn’t even know that. For some reason, that book stayed with me. And I feel like it has an underlying, I don’t know, theme about being an outsider or alienated from the world, I don’t know, is that what it’s about?

Cory: God, I mean, that one came straight out of my subconscious. To kind of recap it very briefly, it’s a story about a guy who grows up in rural Ontario where his father is a mountain and his mother is a washing machine, and the brothers are variously nesting Russian dolls and an immortal vampire, and one of them is an island and so on. One is clairvoyant. And it’s about how he leaves his town in rural North Ontario, moves to Toronto, and moves into this bohemian neighborhood called Kensington Market, where he hooks up with a dumpster diver to build a meshing wireless network through the city. And I wrote that story, I wrote the first 10,000 words while staying at a B&B when my parents were up visiting me when I lived in Northern California. And we went out to Wine Country, and I couldn’t sleep and the first 10,000 words just sort of bashed out of my fingertips. And then I store it on my hard drive for two years. And then I ran into steam on another book that I was working on, I got stuck.

And so I started working on that one again. And then I spent like another year and a half on that one. And then as I was getting towards the end, I got really sad because I thought that the ending I was writing, that I’ve been planning on for most of the time that I’d been working on the book, really wasn’t going to work, and I had a different ending, and I wrote that different ending. And I thought, “Okay, well, now I’m going to have to go back and rewrite the whole book because obviously I’ve just grafted a different head onto this body and it’s going to need a lot of tinkering.” And I turned the book over, printed it out and turned it over and started reading page one that I’d written in that B&B 3:00 in the morning six years before or whatever, and I realized that I foreshadowed the ending that I just written all those years ago, completely unconsciously.

I mean, I actually finished that book, well, at a conference that I was speaking at in Arizona, and I fell asleep while writing the last paragraph and kept typing. And I woke up and there was three sentences of just garbage, [inaudible 01:00:05] my head and deleted and then wrote the actual ending that’s there. And so that’s how kind of totally out of my deep subconscious that book came, and I couldn’t tell you what the hell [inaudible 01:00:19].

Adam: It’ll leave me still wondering. Somebody on Amazon said, “Whether you like this book or not has something to do with how your childhood went.” And I feel that that’s true, but I’m not clear on why. It’s a super interesting book though.

Cory: Yeah, I really enjoyed writing it. And I have in the back of my mind that someday I’d like to write another book that’s a little like that one, but I don’t know what that book would be.

Adam: Well, thank you so much for your time, Cory. It’s been-

Cory: My pleasure. Nice talking to you.

Adam: Great. Take care.

Cory: Bye.

Adam: That was the interview. What did you think? If your hands are free at the moment, ping me on Twitter, let me know that you are listening, or perhaps what you thought of the episode. This was not an episode about Postgres or some programming language but about the technological world we live in, a little bit different than a lot of the episodes I’ve done. So let me know your thoughts, what did you think of it? Until next time, thanks for listening.

Support CoRecursive

Hello,

I make CoRecursive because I love it when someone shares the details behind some project, some bug, or some incident with me.

No other podcast was telling stories quite like I wanted to hear.

Right now this is all done by just me and I love doing it, but it's also exhausting.

Recommending the show to others and contributing to this patreon are the biggest things you can do to help out.

Whatever you can do to help, I truly appreciate it!

Thanks! Adam Gordon Bell